Book a tour

Book a tour

The Battle of the Boyne

In 1690, a major conflict unfolded between the Catholic monarch James II and the Protestant ruler William III, who had ousted James from the English throne in 1688. This decisive battle occurred at Oldbridge in the Boyne Valley and concluded with William emerging victorious. The outcome marked a pivotal moment in James’s quest to reclaim the British crown, solidifying Protestant dominance in Ireland.

The conflict occurred on July 1st, 1690, according to the Julian calendar. However, in Northern Ireland, the commemoration of this event is observed on July 12th, following the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in the 18th century.

William’s forces emerged victorious against James’s predominantly inexperienced army of recruits. The symbolic significance of this battle has elevated it to one of the most renowned conflicts in the history of Britain and Ireland, playing a crucial role in the folklore of the Orange Order. Presently, its commemoration is primarily led by the Protestant Orange Institution in Northern Ireland.

Lead up to the Battle of the Boyne

The pivotal battle served as the conclusive clash in a broader conflict centered around James’s bid to reclaim the thrones of England and Scotland. This aspiration arose from English noblemen inviting James’s daughter and William’s wife, Mary, to ascend the throne. Notably, the event holds significance as a critical juncture in the ongoing struggle between Protestant and Catholic interests in Ireland.

Within an Irish context, the war transformed into a sectarian and ethnic strife, echoing aspects of the Irish Confederate Wars half a century earlier. For the Jacobites, the conflict represented a fight for Irish sovereignty, religious tolerance for Catholicism, and the restoration of lost land ownership. The Catholic upper classes, having suffered substantial losses after Cromwell’s conquest, sought redress for their grievances and autonomy from England under the Catholic King James. Led by Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnel, they had raised an army by 1690, controlling all of Ireland except Ulster. The majority of James II’s troops at the Boyne were Irish Catholics.

The widespread support for James II among the Irish populace stemmed from his 1687 Declaration of Indulgence, also known as The Declaration for the Liberty of Conscience, which granted religious freedom across denominations in England and Scotland. Additionally, James II’s promise to the Irish Parliament of eventual self-determination further solidified his backing.

Conversely, for the Williamites, the war centered on preserving Protestant and English rule in Ireland. Fears of life and property loss under James’s Catholic rule, coupled with apprehensions of a repeat of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 marked by widespread killings, motivated Protestants to support William of Orange. Many Williamite troops at the Boyne, including the formidable irregular cavalry known as the Inniskillingers, were Protestants from Ulster, often referred to as Scots-Irish by contemporaries.

Battle of the Boyne Living History Display

Battle of the Boyne Commanders

The opposing forces in the battle were led by King James II, a Roman Catholic reigning over England, Scotland, and Ireland. On the opposing side stood his nephew and son-in-law, King William III (also known as William of Orange), who had deposed James the year before. James’s loyalists held significant sway over Ireland and its Parliament. Additionally, James received support from his cousin, Louis XIV, who aimed to prevent a hostile monarch from occupying the English throne. Louis dispatched 5,000 French troops to Ireland in support of the Irish Jacobites. Meanwhile, William, serving as the Stadtholder of the Netherlands, could enlist Dutch and allied troops from Europe, as well as forces from England and Scotland.

James, an experienced officer who had demonstrated bravery in European conflicts, notably at the Battle of the Dunes (1658), exhibited signs of panicking under pressure and making impulsive decisions, possibly attributed to the onset of dementia that would later fully manifest. While William, a seasoned commander, lacked a significant track record of major battle victories, often experiencing stalemates. Some modern historians argue that William’s success against the French relied more on tactical maneuvers and diplomacy than on military force. His diplomatic skills had led to the formation of the League of Augsburg, a multinational coalition resisting French aggression in Europe. From William’s perspective, assuming power in England and conducting the campaign in Ireland was just another facet of the broader conflict against King Louis XIV.

Among James II’s key commanders were Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, the powerful Lord Deputy of Ireland and James’s main supporter in the country, along with the French general Lauzun. William’s second-in-command was the Duke of Schomberg, a 75-year-old professional soldier originally from Heidelberg, Germany. Schomberg, formerly a Marshal of France, had left the country in 1685 due to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, as he was a Huguenot.

Battle of the Boyne Armies

The Williamite army present at the Battle of the Boyne numbered approximately 36,000, consisting of troops hailing from diverse nations. About 20,000 soldiers had been stationed in Ireland since 1689 under the command of Schomberg, while William himself arrived in June 1690 with an additional 16,000 troops. Notably, William’s forces were notably better trained and equipped compared to James’s army. The elite infantry within the Williamite ranks originated from Denmark and the Netherlands, comprising professional soldiers armed with state-of-the-art flintlock muskets. A significant contingent of French Huguenot troops fought alongside the Williamites. William held a less favorable opinion of his English and Scottish troops, except for the Ulster Protestant irregulars who had defended Ulster in the preceding year. The English and Scottish soldiers were considered politically unreliable, given that James had been their legitimate monarch just a year prior. Additionally, these troops had been raised recently and had limited battle experience.

On the Jacobite side, approximately 24,000 soldiers comprised their forces. James commanded several regiments of French troops, but the majority of his army consisted of Irish Catholics. The Irish cavalry among the Jacobites, drawn from the dispossessed Irish gentry, demonstrated high-caliber performance during the battle. However, the Irish infantry, primarily comprised of hastily trained peasants pressed into service, lacked the training of seasoned soldiers. They were ill-equipped, with only a minority possessing functional muskets. In fact, some carried nothing more than farm implements such as scythes at the Boyne. Additionally, the Jacobite infantry with firearms used the outdated matchlock musket.

The Battle

On June 14th, 1690, William landed in Carrickfergus, Ulster, and subsequently marched south with the aim of capturing Dublin. James strategically positioned his defensive line along the River Boyne, approximately 30 miles (48 km) from Dublin. The Williamite forces reached the Boyne on June 29th, and on the eve of the battle, William narrowly avoided injury when a Jacobite cannonball wounded him in the shoulder while he surveyed the river crossings his troops would use.

The Battle of the Boyne unfolded on July 1st (Julian calendar) or July 11th (Gregorian calendar), centering on the control of a ford near Drogheda, about 1.6 miles (2.5 km) northwest of Oldbridge. William directed a quarter of his forces to cross at Roughgrange, west of Donore, while the majority confronted the main ford near Oldbridge. James, concerned about being outflanked, committed two-thirds of his troops and most of his artillery to counter the Roughgrange crossing.

Unbeknownst to both sides, a swampy ravine at Roughgrange prevented engagement, resulting in a standoff. Williamite forces later embarked on a detour that nearly cut off the Jacobite retreat at Naul. At the primary ford, the elite Dutch Blue Guards led William’s infantry, successfully crossing the river but facing resistance from Jacobite cavalry during a counter-attack. While securing Oldbridge, some Williamite infantry attempted disciplined volley fire against successive cavalry attacks but were eventually scattered. In this phase, William’s second-in-command, the Duke of Schomberg, and George Walker were killed.

The Williamites could only resume their advance after their own horsemen crossed the river and held off Jacobite cavalry, eventually regrouping at Donore. The Jacobites, retiring in good order, faced the opportunity of being trapped at the River Nanny in Duleek, but a successful rear-guard action impeded William’s troops.

Despite involving 60,000 participants, casualties were relatively low, with around 2,000 deaths, the majority being Jacobites. William’s army suffered more wounded, and the lack of pursuit-related casualties was unusual for the time. The Jacobites’ demoralization from the retreat contributed to their loss. The Williamites entered Dublin two days after the battle, while the Jacobite army withdrew to Limerick, enduring an unsuccessful siege.

Following his defeat, James swiftly departed Dublin for Duncannon and ultimately returned to exile in France, leaving his relatively unharmed army behind. James’s abrupt departure angered his Irish supporters, who continued fighting until the Treaty of Limerick in 1691.

Battle of the Boyne Aftermath

At the time, the Battle of the Boyne was somewhat overshadowed in England by the French victory over an Anglo-Dutch fleet at the Battle of Beachy Head, a more immediately consequential event. Only on the continent was the Boyne acknowledged as a significant triumph. Its importance lay in being the inaugural decisive victory for the League of Augsburg, marking the first-ever alliance between the Vatican and Protestant nations. This victory spurred more countries to join the alliance, effectively dispelling concerns of a potential French conquest of Europe.

The Battle of the Boyne held strategic importance for both England and Ireland. It signaled the end of James’s aspirations to reclaim the throne through military means, likely securing the success of the Glorious Revolution. In Scotland, news of this defeat briefly subdued the Highlanders supporting the Jacobite Rising led by Bonnie Dundee. In Ireland, the Boyne reassured the Jacobites of their capacity to resist William, but it ultimately constituted a general triumph for William. To this day, the Protestant Orange Order commemorates the victory on the Twelfth of July.

The Treaty of Limerick displayed considerable generosity toward Catholics, permitting most landowners to retain their property if they pledged allegiance to William of Orange. It also allowed James to return to France with a certain number of his soldiers. However, in England, Protestants were displeased with this leniency towards Catholics, especially as they gained strength and resources. Consequently, the introduction of penal laws followed, prohibiting Catholics from owning weapons, reducing their land holdings, and barring them from working in the legal profession.

Battle of the Boyne Commemoration

Initially, Irish Protestants observed the commemoration of the Battle of Aughrim on July 12th, signifying their triumph in the Williamite war in Ireland. Aughrim, occurring a year after the Battle of the Boyne, resulted in the decisive defeat of the Jacobite army, tipping the scales in favor of the Williamites. The Battle of the Boyne, originally taking place on July 1st in the Julian calendar, was considered less significant, ranking third after Aughrim and the anniversary of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 on October 23rd. The focal point of “The Twelfth” celebration was not William’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne, but rather the defeat of the Catholic Irish at Aughrim, erasing fears of relinquishing the planted lands.

In 1752, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in Ireland led to the incorrect placement of the Boyne on July 12th instead of Aughrim (the accurate equivalent date being July 11th). Even after this adjustment, “The Twelfth” continued to commemorate Aughrim. However, with the founding of the Orange Order in 1795 during sectarian violence in Armagh, the emphasis of parades on July 12th shifted to the Battle of the Boyne.

Despite the change in the calendar, and the possibility of aligning the anniversary of the Boyne with the new July 1st date or celebrating the revised Aughrim anniversary, the Orangemen, wary of anything associated with Papist connotations, opted to persist with marching on July 12th.

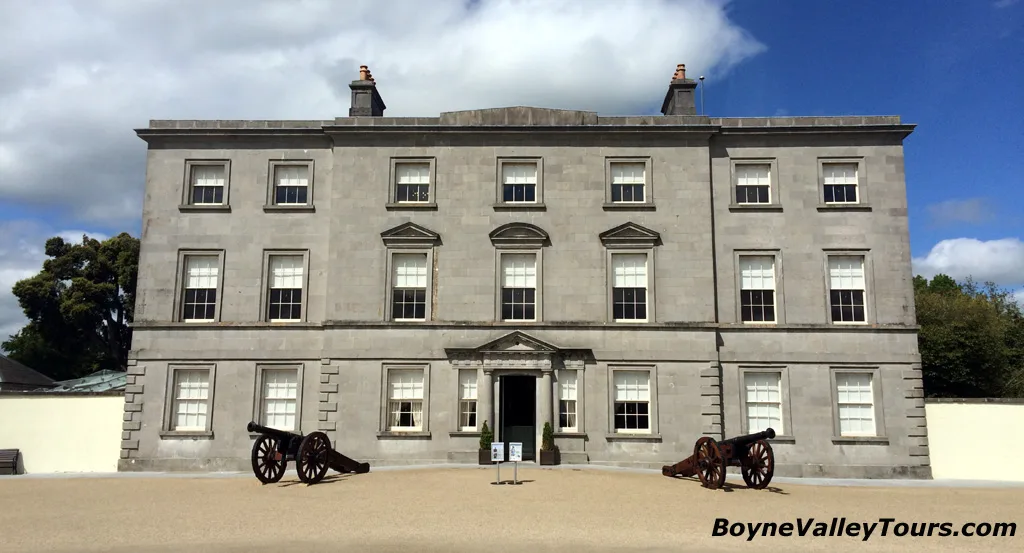

Battle of the Boyne Visitor Center at Oldbridge

The expanse where the Battle of the Boyne unfolded stretches broadly to the west of Drogheda. The Visitor Center at Oldbridge House is situated approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the primary crossing point. On April 4th, 2007, reflecting an improvement in relations between unionist and nationalist groups, the recently elected First Minister of Northern Ireland, Reverend Ian Paisley, received an invitation from the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern to visit the battle site later that year. Responding to the invitation, Paisley expressed that such a visit would exemplify the progress made and provide an opportunity to celebrate and learn from the past for the benefit of future generations.

On May 10th, the visit materialized, during which Paisley presented the Taoiseach with a Jacobite musket in reciprocation for Ahern’s gift at the St. Andrews talks—a walnut bowl crafted from a tree sourced from the battle site. As part of the occasion, the two leaders planted a new tree in the grounds of Oldbridge House to symbolize the significance of the visit.

Oldbridge House, Walled Garden

Oldbridge House restored Victorian Walled Garden, Glasshouse, a unique sunken Octagonal Garden and a Garden Exhibition in the Bothy.

Newgrange & Boyne Valley

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees

Boyne Valley Castles & Abbeys

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees

Meath Megalithic Sites

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees

Glendalough & Scenic Wicklow

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees

Wicklow Gardens & Scenery

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees

Cruise Excursions

8hrs | €650 + Booking Fees